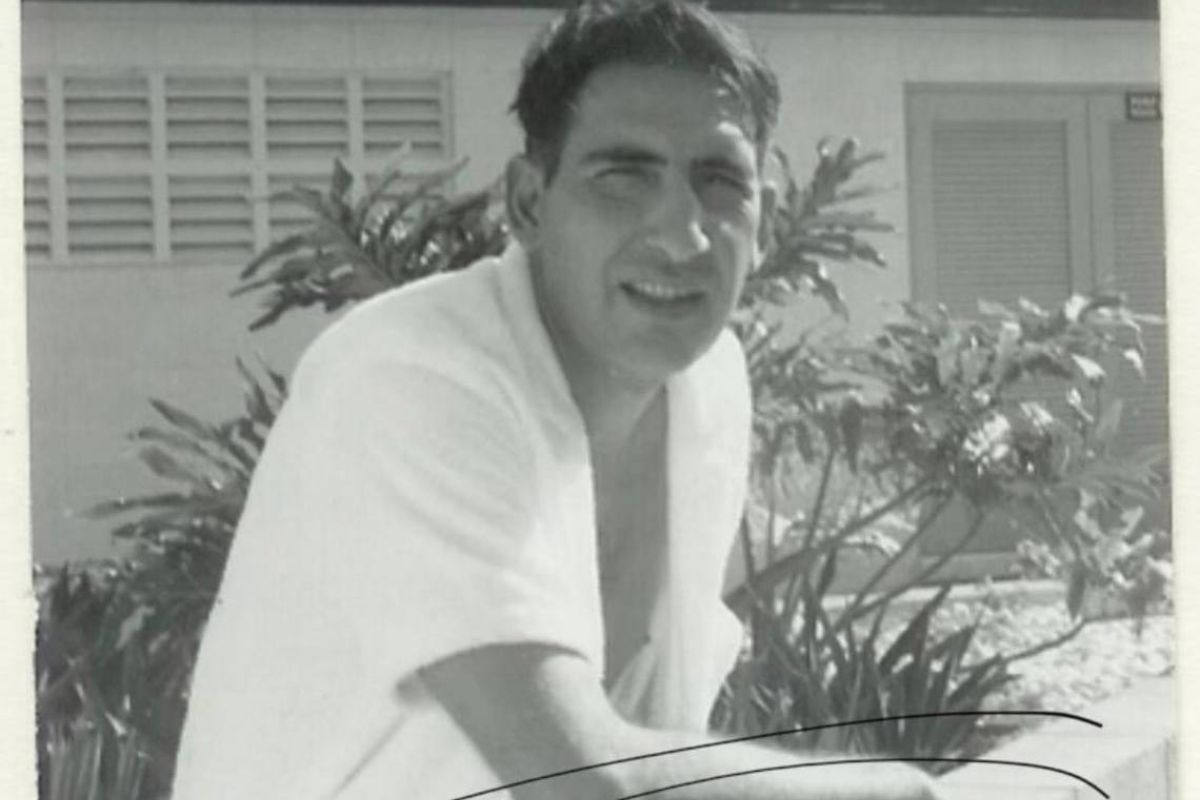

Mike Gonzalez, a police detective in Miami, was the best at solving murders for more than 40 years. Gonzalez solved cases the old-fashioned way by following up on leads, talking to witnesses, and getting suspects to confess. This was long before DNA tests and video surveillance.

He found a man who wouldn’t pay a 10-cent toll, shot and killed a Florida Highway Patrol trooper, and then went after the man again. During an investigation into another murder, he found a huge cocaine network. More than a decade after a woman’s body was found naked and strangled in her bed, the murderer confessed to Gonzalez and said he had killed another person two years earlier.

Edna Buchanan, a famous crime reporter and author for the Miami Herald, once said, “He has solved more murders than anyone else in the world, except for Simon Wiesenthal, the Nazi hunter.”

Gonzalez died last week after a short illness at his home in South Miami-Dade. He had been retired from the homicide bureau in Miami for more than 30 years. His wife Gloria was with him. He was 95.

“Mike has never used today’s DNA successes to solve a case. But he solved more murder cases with his words than dozens of DNA investigators do today, said retired Lt. Jerry Green of the Miami Police Department. “Mike lived a long life and was very important to the MPD and Miami. RIP Mike.” He was born in Brooklyn, New York, on December 21, 1926.

During World War II, he was in the Merchant Marines. After the war, he moved to Miami in 1946 and joined the police force there five years later. By 1956, he had moved from the streets to killing people. There, as Miami went from being a quiet town to one of the world’s biggest drug-smuggling hubs, his reputation and number of cases quickly grew.

In 1980, while working on a case about the “execution-style” deaths of Aurea Poggio, Miami’s director of cultural affairs, and three others, Gonzalez found a large cocaine network. He also quickly solved a case from 1984 in which George Napoles’ head was hit with a baseball bat on the Rickenbacker Causeway and the woman he was with was taken and raped. It was hard to find hints.

Gonzalez went public because the killer’s car didn’t have a back window. Ricky Roberts was charged with the crime a day later. The jury said he should be killed. Gonzalez became a local law enforcement legend because he was very patient and had a good eye for details. He made friends with other detectives, medical examiners, reporters, and even the people he was looking for. Above all, his former coworkers said, Gonzalez tried to change the minds of killers by being kind to them. As a reminder, he kept a small sign in a frame on the wall of his office. It said, “Be kind.”

Confesor Gonzalez, a former Miami homicide detective, called him the “mentor of mentors.” “He was pleasant. But he wasn’t a wimp. Gonzalez said, “He was a strong man with a strong personality, and you respected him. Even though they weren’t related, Confessor would call Mike “uncle” affectionately. “He worked hard to earn their loyalty and respect.” Nelson Andreu, a retired Miami detective who helped investigate killers connected to the notorious Cocaine Cowboys, called him “one of my best mentors” and the “dean of Miami homicide.”

“When it came to interrogations, he always said, ‘When you think you’re about to give up because you’re not getting anywhere, give it five or ten minutes,'” Andreu said. “That extra time and the fact that we didn’t give up helped us get so many confessions.” As the mentor, Gonzalez pushed smart officers on the street to investigate a homicide. This helped him build a team of investigators who became known for catching killers. One of them is Delrish Moss, who worked for the Miami Police Department for many years, moving from homicide detective to department spokesman before becoming the police chief in troubled Ferguson, Missouri. He says he owes his career to Gonzalez. “Mike cared a lot about me and my growth, and he made sure I went to a lot of schools,” he said.

“Former Miami homicide detective Confesor Gonzalez called him the ‘mentor of mentors.’”

Read more at: https://t.co/1nubfotuye https://t.co/072Br99rg7

— Jenny Staletovich (@jenstaletovich) December 7, 2022

Moss, a Black officer, remembered when Gonzalez asked him kindly about a picture of civil rights leader Malcolm X that he kept on his desk, even though some other cops were talking about it behind their backs. “He came over and asked for more information. Moss said, “He then started reading books about Malcolm X.” Gonzalez eventually moved up through the ranks. In 1988, when a young detective named Eunice Cooper joined the unit, he was the unit’s lieutenant.

“When I started working in homicide, Mike was a hero. Cooper, who now works as an investigator for the Miami-Dade State Attorney’s Office, said, “It was an honor to be around him.” She remembered that Gonzalez was always cool and collected but could be strict. On her second day in the murder, there was a mix-up with the paperwork for her transfer. Gonzalez heard Cooper on the phone with a patrol supervisor who told her to do roll call. Gonzalez grabbed her phone and yelled at the patrol supervisor. He said that she was now a murderer. Stay away.

Cooper said, “He was fiercely protective of his people.” Gonzalez told the Herald that he had worked on more than 1,000 murder cases when he retired in 1991. It kept him fit. In 1981, a suspect in a shooting who was bleeding crashed into a house in South Miami after being chased. Then he got out of the car and started running away. At the time, Gonzalez, who was 54, caught him. He gave up when he saw Gonzalez. The man had been arrested by the detective years ago. “I’ve never shot a person. I’ve never been shot. “I’ve put more dangerous people in jail than anyone else,” Gonzalez said.

Even though he was successful, the cases he couldn’t solve were the ones that stayed with him the most. Amy Billig, who was 17 at the time and went missing in Coconut Grove in 1973, is probably the most well-known of these cases. After almost 50 years, the case has not been solved. He told the Miami Herald, “I can’t stop thinking about the ones I didn’t solve.” “The families of the people who died, the way it happened, and how close we came to making it but didn’t.” But Robert Gonzalez said his brother was proud of his “long, satisfying career.”

“I don’t think he missed any [police work]. He wasn’t the type to keep thinking about old cases. Robert Gonzalez said, “He was very modest.” It was a promotion and a change to a daytime shift that ended his long and successful career. He finally found a case he couldn’t solve: how to avoid rush-hour traffic. Two years later, in 1991, he gave up his badge because it took him more than an hour to get from his home in South Dade to the Miami Police Department.

His family said that over the next 30 years, he worked on his artistic side by making stained glass and metal sculptures. Gonzalez is survived by his wife Gloria. His brother Bob Gonzalez, his daughters Joan McMath and Teresa Wright, and his son Charles Gonzalez. And many grandchildren. His family said that Gonzalez did not want there to be a funeral.

For Daily updates, stay connected to our website NogMagazine.com