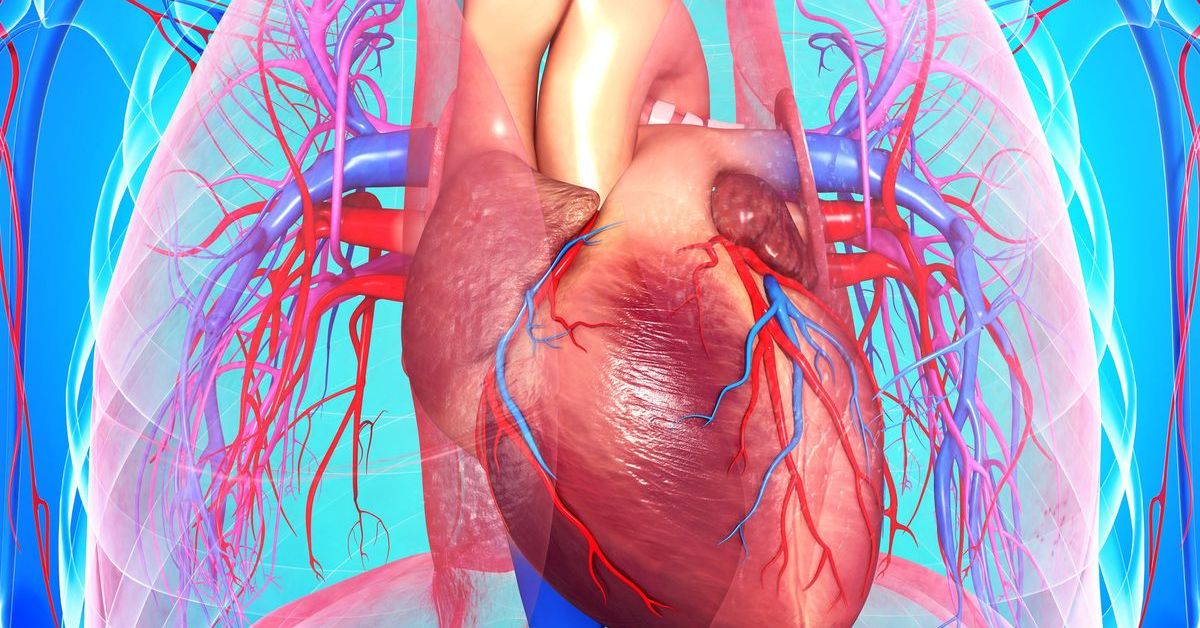

New research shows that a lower frequency of salt in the diet is linked to a lower risk of heart disease (CVD).

A new study published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology found that putting less salt in food is linked to a lower risk of heart disease, heart failure, and ischemic heart disease. The study shows that reducing salt intake could improve heart health even for people who eat a DASH-style diet.

Previous research has shown that eating a lot of sodium can make you more likely to get high blood pressure, a major risk factor for heart disease. But previous studies that looked into this link came to different conclusions because there were no good ways to measure long-term sodium intake. Recent studies suggest that the amount of salt a person puts in their food can be used to estimate how much sodium they will take in over time.

Lu Qi, MD, Ph.D., HCA Regents Distinguished Chair and professor at the School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine at Tulane University in New Orleans, said, “Overall, we found that people who don’t add a little extra salt to their food very often have a much lower risk of heart disease events, regardless of lifestyle factors and pre-existing disease.”

“We also found that people were least likely to get heart disease when they ate a DASH diet and didn’t add salt very often. This is important because reducing the amount of salt added to food, but not getting rid of salt altogether, is a very changeable risk factor that we can try to get our patients to make without too much trouble.

Latest News

- Study Says, Heavy Coffee Drinkers With High Blood Pressure Increase Risk of death

- China Estimates 250 million COVID-19 Cases In 20 Days

In this study, the authors looked at 176,570 people from the UK Biobank to see if the amount of salt they put on their food was linked to their risk of getting heart disease. The study also looked at the link between how often salt is added to food and the DASH diet in terms of the risk of heart disease.

At the start of the study, a questionnaire was used to find out how often people put salt on their food, excluding salt used in cooking. Participants were also asked if they had made any big changes to their diet in the last five years, and they had to fill out 1–5 rounds of 24-hour dietary recalls over three years.

The DASH-style diet was made to prevent high blood pressure by cutting back on red and processed meats and putting more emphasis on vegetables, fruit, whole grains, low-fat dairy, nuts, and legumes.

Even though the DASH diet has helped reduce the risk of heart disease, a recent clinical trial found that combining the DASH diet with a lower sodium intake was even better for specific biomarkers of heart damage, strain, and inflammation. The researchers made a modified DASH score that didn’t take sodium intake into account. It was based on seven foods and nutrients emphasized or downplayed in the DASH-style diet.

Information about heart disease events was gathered from medical histories, hospital stays, questionnaires, and death registers.

Overall, study participants who added less salt to their food were more likely to be women, white, have a lower body mass index, drink moderately, not smoke, and be more active. They also had more people with high blood pressure and kidney disease, but fewer people with cancer.

These people were also more likely to follow a DASH-style diet and eat more fruits, vegetables, nuts and legumes, whole grains, low-fat foods, and low-sugar drinks, but less red or processed meats than those who added salt to their food more often.

The link between adding salt to food and the risk of heart disease was stronger in people with lower incomes and in people who were still smoking. Heart disease events were less likely to happen in people whose modified DASH diet score was higher.

In a related editorial comment, Sara Ghoneim, MD, a gastroenterology fellow at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, wrote that the study is promising, builds on previous reports, and hints at the possible effect of long-term salt preferences on total cardiovascular risk.

“A big problem with the study is that people said how often they put salt on their food, and the only people who took part were from the UK. This makes it hard to apply the results to other groups of people who eat differently,” Ghoneim said.

“The results of this study are encouraging and will help us learn more about how behavior changes related to salt affect heart health.”

Forward this news to your friends and stay connected to our homepage NogMagazine.com for more updates.