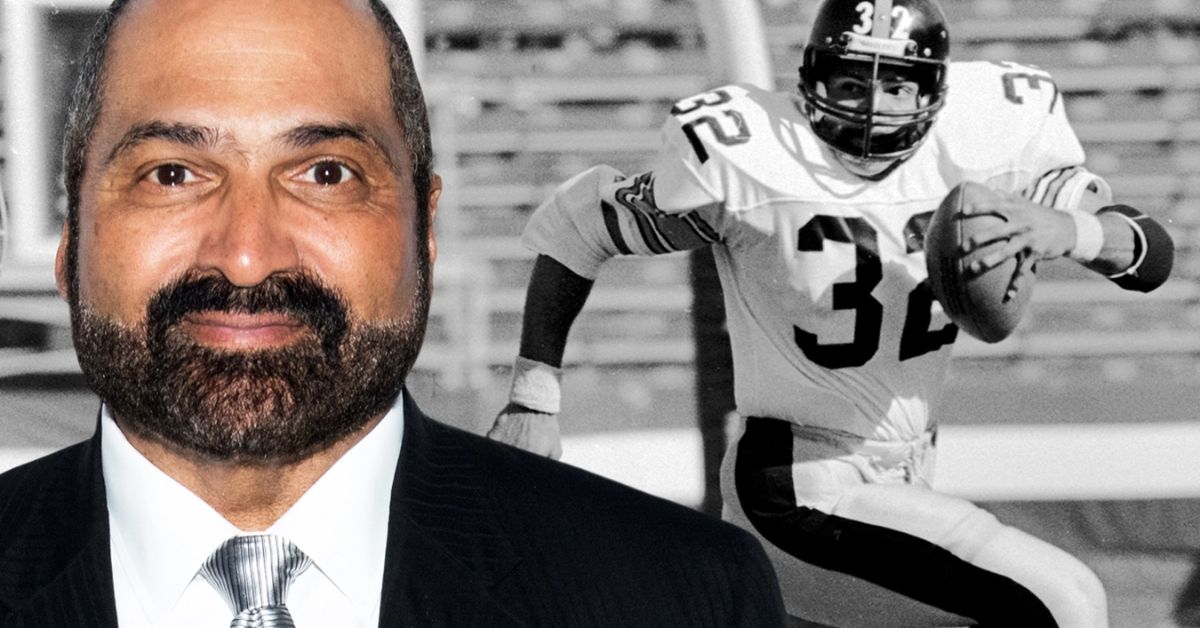

Franco Harris, the running back in the Hall of Fame and whose quick thinking led to the “Immaculate Reception,” which is considered the most famous play in NFL history, has died. He was 72.

Dok, Harris’s son, told The Associated Press that his dad died in the middle of the night. No reason was given for the death.

His death happened two days before the 50th anniversary of the play that gave the Pittsburgh Steelers the boost they needed to become one of the best teams in the NFL. It also happened three days before the team was going to retire his number 32 at halftime of their game against the Las Vegas Raiders.

In a statement, Steelers president Art Rooney II said, “It’s hard to find the right words to describe what Franco Harris meant to the Pittsburgh Steelers, his teammates, the city of Pittsburgh, and Steelers Nation.” “Franco made people happy on and off the field for 50 years, starting with his rookie year, which included the “Immaculate Reception.” He gave back in so many ways and never stopped. He helped so many people, and so many people loved him. During this hard time, our thoughts and prayers are with his wife Dana, his son Dok, and the rest of his family.”

Harris ran for 12,120 yards and won four Super Bowl rings with the Steelers in the 1970s. This dynasty began in earnest when Harris decided to keep running during a last-second pass by Pittsburgh quarterback Terry Bradshaw in a 1972 playoff game against Oakland.

With 22 seconds left in the fourth quarter and the Steelers down 7-6 and on fourth-and-10 from their 40-yard line, Bradshaw moved back and threw deep to running back John “Frenchy” Fuqua. When Fuqua and Jack Tatum, a defensive back for Oakland, collided, the ball flew back toward midfield and Harris.

Latest News

- Charlbi Dean Cause Of Death Revealed After Sudden Passing At 32

- tWitch Cause of Death: How Did He Die?

Harris kept his legs moving while almost everyone else on the field stopped. He grabbed the ball just a few inches above the Three Rivers Stadium turf near the Oakland 45, then beat a few stunned Raiders defenders to give the Steelers their first playoff win in the team’s 40-year history.

After the Immaculate Reception was voted the best play in NFL history during the league’s 100th anniversary season in 2020, Harris said, “That play represents our teams of the 1970s.”

Even though the Steelers lost to the Miami Dolphins the following week in the AFC Championship Game, Pittsburgh was on its way to becoming the best team of the 1970s. In 1974 and 1975, and again in 1978 and 1979, the Steelers won back-to-back Super Bowls.

Roger Goodell, the commissioner of the NFL, said in a statement, “We are shocked and saddened by the sudden death of Franco Harris.” “He was a Hall of Fame running back who was an important part of the Steelers’ dominance in the 1970s, but he was so much more than that. He was a kind person who touched a lot of people in Pittsburgh and the NFL as a whole. Franco changed people’s feelings about the Steelers, Pittsburgh, and the NFL. Fans of the Steelers, his teammates, and the city of Pittsburgh will always remember him. His wife, Dana, and their son, Dok, are in our thoughts and prayers.“

Steelers coach Mike Tomlin said, among other things, that he admired Harris. “So much can be learned from how he acted and took on the responsibilities of being Franco for Steeler Nation, this community, and Penn State fans. He did everything with grace, style, patience, and time for other people.“

“No matter how many compliments he got, he always gave credit to other people,” defensive line captain Cam Heyward told Harris on his podcast on Tuesday afternoon. “It was amazing how he treated people after him with respect. He always treated every player and person in the city with the utmost respect. When you talk to Franco, you can’t help but feel humble. Today, we lost a good one.”

Harris, a 6-foot-2, 230-pound Penn State player, was in the middle of everything. He ran for a then-record 158 yards, and a touchdown as Pittsburgh beat Minnesota 16-6 in Super Bowl IX. This helped him win the Most Valuable Player award for the game. He scored at least one touchdown in three of the four Super Bowls he played in, and his 354 career rushing yards on the NFL’s biggest stage are still the most ever.

Harris was born in Fort Dix, New Jersey, on March 7, 1950. He went to Penn State for college and played backfield, where his main job was to make holes for Lydell Mitchell. The Steelers, led by Hall of Fame coach Chuck Noll, were in the final stages of rebuilding when they picked Harris with the 13th overall pick in the 1972 NFL draught.

“When [Noll] drafted Franco Harris, he gave the offense heart, discipline, desire, and the ability to win a championship in Pittsburgh,” said Lynn Swann, a Steelers Hall of Fame wide receiver who often shared rooms with Franco Harris on team road trips.

Harris’s effect was felt right away. In 1972, when he was a rookie, he ran for 1,055 yards and 10 touchdowns, a team record at the time. This helped the Steelers make the playoffs for the second time in the team’s history.

BREAKING NEWS: Hall of Fame Steelers running back Franco Harris has died at 72.

https://t.co/O138cOlg3E— KDKA (@KDKA) December 21, 2022

The city’s large Italian American population welcomed Harris right away. Two local businessmen started what became known as “Franco’s Italian Army,” a reference to Harris’ roots as the son of an African American father and an Italian mother.

Harris became famous because of “The Immaculate Reception,” but he usually preferred to let his play, not his words, do the talking. On a team with prominent personalities like Bradshaw, defensive tackle Joe Greene, and linebacker Jack Lambert, the quiet Harris was the engine that made Pittsburgh’s offense go for 12 seasons.

He ran for more than 1,000 yards in a season eight times, including five times when he played 14 games. He ran for another 1,556 yards and 16 touchdowns in the playoffs, which is second all-time behind Emmitt Smith.

Harris stressed that, despite his big numbers, he was just one part of a fantastic machine.

“You see, each player brought their little piece to that great decade,” Harris said in his Hall of Fame speech in 1990. “Each player had their strengths and weaknesses. Each had their way of thinking and doing things. But then it was incredible. Everything came together and stayed together to make the best team ever.”

Harris was also always there for his teammates. In the second half of the 1978 Super Bowl, Dallas linebacker Thomas “Hollywood” Henderson hit Bradshaw late, which Harris thought was against the rules. Harris told Bradshaw to give him the ball on the next play. Harris only had to run up the middle 22 yards, right by Henderson, to score a touchdown that gave the Steelers an 11-point lead they would not give up on their way to their third championship in six years.

Harris had a lot of success, but his time with the Steelers ended badly when he refused to work during training camp before the 1984 season. Noll relied so much on Harris for so long that he was famously asked about Harris’s absence from camp at Saint Vincent College. He replied, “Franco, who?”

Harris joined Seattle, but he only ran for 170 yards in eight games before he was let go in the middle of the season. After Walter Payton and Jim Brown, he left the NFL as the third-best rusher of all time.

Harris said in 2006, “I don’t even think about that anymore.” “I’m still black and gold.”

Harris stayed in Pittsburgh after he retired. He opened a bakery and got involved in many charities. He was the chairman of “Pittsburgh Promise,” which gives Pittsburgh Public School students a chance to earn college scholarships.

Pat Freiermuth, a fellow Penn State graduate, announced by Harris at the 2021 NFL draught, remembered going to dinner with Harris and spending time with him at Penn State’s spring game. “It’s sad to hear the news this morning, especially since there are plans to honor Franco’s famous NFL catch this weekend,” Freiermuth said. “He might not be there in person, but he will be there in heaven.“

Harris’s wife, Dana Dokmanovich, and his son are the only ones who will miss him.

Keep following our site NogMagazine.com for the latest updates.